This is my fourth post in a series of posts going ‘Back to Basics‘, re-examining techniques and ideas introduced on teacher training courses.

What is eliciting?

The British Council Teaching English website defines elicitation as ‘a technique by which the teacher gets the learners to give information rather than giving it to them’.

Why do we elicit?

Eliciting language from the students can help in creating a more learner-centred classroom, getting the students more involved and engaged in the lesson. Rather than spoon-feeding the students, it makes them more active in the learning process. Eliciting builds on the students’ existing knowledge, linking old and new information.

When do we need to elicit language?

Eliciting language can happen in many moments during a lesson, such as:

- Vocabulary – in a receptive skills lesson (pre-teaching items before reading or listening to a text).

- Language focus – eliciting features of meaning, form and pronunciation of the target language.

- General knowledge – finding out what students know about a topic during a lead in.

This post focuses on eliciting vocabulary during a pre-teaching stage of a receptive skills lesson.

The value of pre-teaching is an issue which tends to polarise experienced teachers. It often features quite predominantly on a CELTA course, but as teachers gain experience, many tend to find themselves pre-teaching less, and instead encouraging learners to deduce meaning from context. For more on this debate, see this IH Journal article by Chris Ozog, and this blog post by Rachel Roberts.

But for now, let’s just remind ourselves what pre-teaching is and why one might decide to do it:

What is pre-teaching?

The British Council Teaching English website defines pre-teaching as ‘the teaching of the language learners need before an activity’. It is commonly done in a reading or listening lesson before the learners are exposed to the text for the first time. There may be important words in the text which are beyond the learners’ level, and could block understanding; focusing quickly on these words before being given the text can support the learners, providing scaffolding. Otherwise, the teacher may find themselves having to teach the same word again and again to many different individuals as they come across it in a reading text; it can also help to reduce the need for students to stop and reach for a dictionary when they find a new word, speeding things up somewhat.

What to pre-teach?

Naturally, when teachers are deciding what to pre-teach, they often simply look for difficult words in the text. A little more thought and judiciousness is required though to ensure this stage is valuable use of lesson time. Items to pre-teach might include:

- An item which the student needs to understand in order to complete the task which has been set (e.g. it is in the question, or is necessary to answer the question).

- An item which is key to understanding the overall meaning of a text.

- An item which assumes the reader has specific cultural knowledge.

- An item which occurs frequently in the text.

Of course, it would be unadvisable to pre-teach all the ‘difficult’ words which appear in a text. This language is being taught to provide some support in helping the learners process the text; they need to be able to tolerate and deal with ambiguity too.

Techniques for eliciting vocabulary

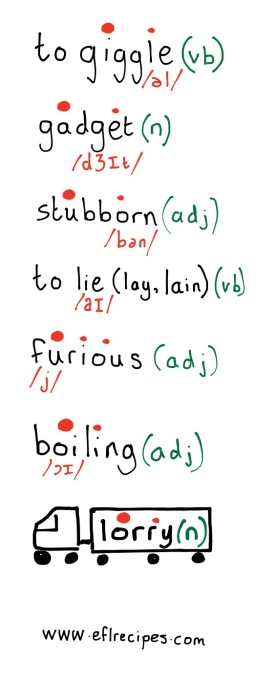

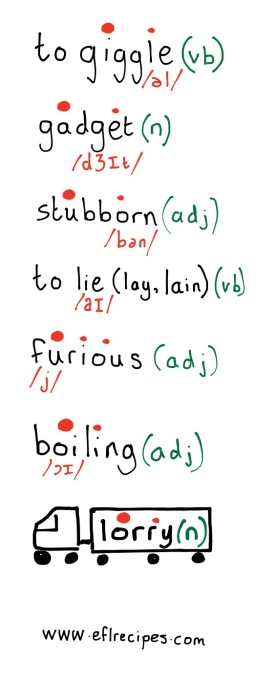

Definitions – “This is when a person laughs in a nervous or silly way; young children might do this.” – to giggle

Exemplification – “A mobile phone, a tablet, a GPS (Sat-Nav), an MP3 player, an e-reader.” – a gadget

Context/Anecdote (Useful for more abstract items) – “One of my friends has very strong views and he never changes his opinions, even when it is clear to everyone else that he is wrong; what can we call a person like this?” – stubborn

Mime – Teacher lies on the floor – to lie

Synonyms – “This means the same as very angry.” – furious

Antonyms – “What’s the opposite of freezing?” – boiling

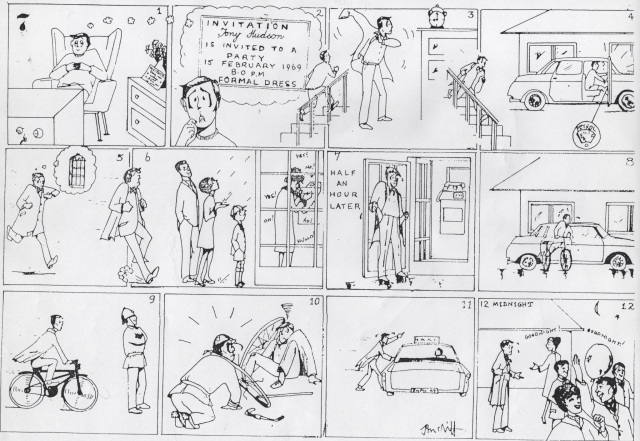

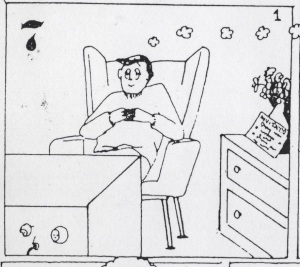

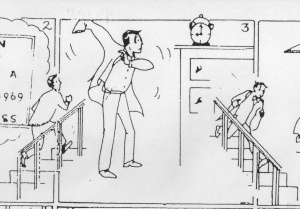

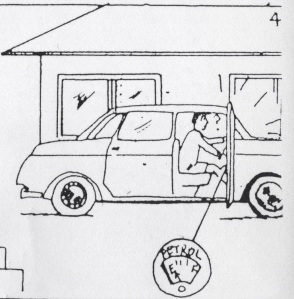

Flashcards/visuals/drawings/realia – Teacher shows a picture of a lorry, draws one on the board, or brings a toy lorry into class – lorry

How can we make eliciting effective?

Go from meaning to word (not word to meaning) – rather than asking “What does ‘crew‘ mean?”, ask “What do we call all the people who work on an aeroplane or a boat?”. In the first example, the teacher is eliciting meaning, which helps few – what can often happen in this situation is that a student who already knows the word offers the answer, leaving those who didn’t know the word with little information about meaning; the teacher here is ‘flying with the fastest’. Going with the concept first, as in the second question above, keeps everyone at the same pace so meaning is clear before the new item is dropped into the gap.

Praise good contributions – maybe you are trying to elicit ‘huge’ and a student comes out with ‘enormous’. Rather than telling the student that they are wrong, give them credit and say something like “that’s a very similar word, does anyone know another one? … beginning with ‘h’?”

Don’t flog a dead horse – if it becomes clear that the students have understood the concept but just don’t know the word, then provide the item yourself and concept check to ensure they are clear on meaning. Drop the language item in to fill the gap in their lexis.

Eliciting is not a game of charades – Avoid the temptation to say things like “It sounds like ‘wiggle'”, when eliciting ‘giggle’ – Meaning is key, form comes later.

Keep it snappy – remember this language is not the target language of the lesson, it is just being taught for recognition. A 15-minute pre-teaching stage in a 40-minute reading or listening lesson does not contribute much to meeting the main lesson aim and is not efficient use of valuable classroom time. This stage can interrupt the flow of a lesson, and students might wonder how the seemingly random words being taught are connected, so to avoid this, be snappy with it and limit it to only the essential items (usually no more than 3 or 4, and no more than a minute or so for each).

Check meaning – after meaning has been conveyed, use concept checking techniques to ensure that the students have got it. For help with concept checking, see my previous post (Concept Checking Revisited).

Stages of effective eliciting

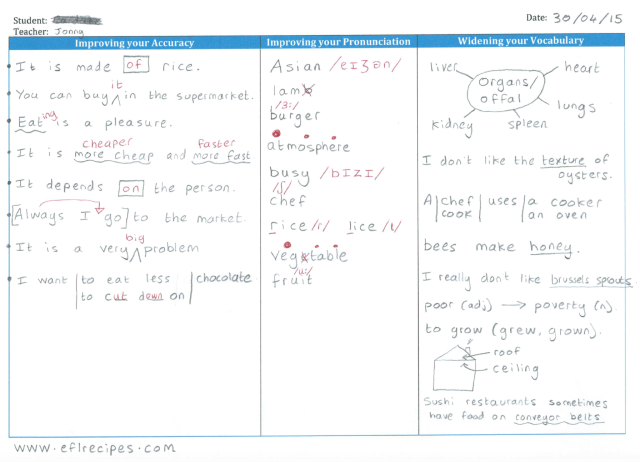

Convey

Use a variety of techniques to provide a balance of focus and pace.

Check

Use concept checking techniques to ensure students have understood the meaning.

Model

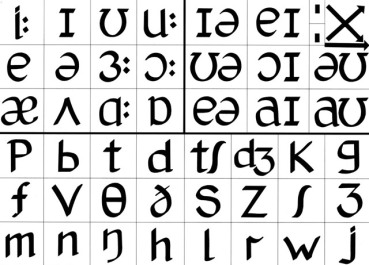

Provide, or elicit from a student, a clear model of the pronunciation.

Drill

Allow students to practise saying the item, first together with others (choral drilling), then nominating students randomly so you can focus on individual learner problems (individual drilling).

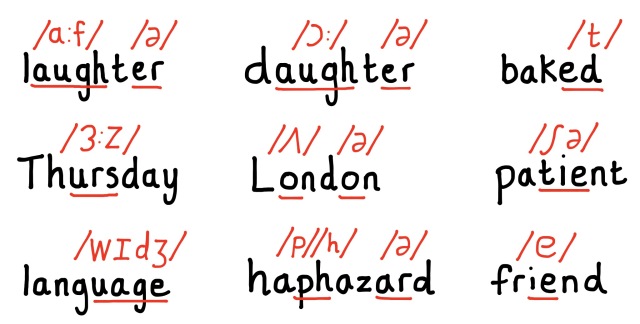

Board

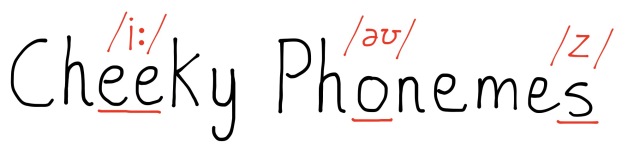

Provide a written model on the board for students to copy and have a written record in their notes. Eliciting and boarding the part of speech, word stress and any tricky sounds is useful here so the students can have a record of how to use and say the item. See a previous post (Cheeky Phonemes) for more tips on highlighting tricky sounds on the board.

Concluding thoughts

In summary, my top tips for effective eliciting and pre-teaching would be:

- Think carefully about why you are pre-teaching language – is it really necessary?

- Remember the stages: Convey -> Check -> Model -> Drill -> Board

- Meaning is key

- Be efficient and keep it snappy!

It is common practice in many educational institutions for teachers to be observed just once a year. This annual observation can be a stressful experience; often high stakes with the outcome directly linked to performance management. As a result, teachers can feel under pressure to ‘perform’ and deliver a lesson which bears little resemblance to what happens in their day-to-day teaching; quite often they will pull out a lesson which has been well rehearsed. The whole process is rather unnatural – writing lengthy and detailed lesson plans with carefully thought out aims, learning outcomes, anticipated problems and minute-by-minute details on procedure. In contrast, many experienced teachers will usually just write a brief running order as a lesson plan for their regular, unobserved classes.

It is common practice in many educational institutions for teachers to be observed just once a year. This annual observation can be a stressful experience; often high stakes with the outcome directly linked to performance management. As a result, teachers can feel under pressure to ‘perform’ and deliver a lesson which bears little resemblance to what happens in their day-to-day teaching; quite often they will pull out a lesson which has been well rehearsed. The whole process is rather unnatural – writing lengthy and detailed lesson plans with carefully thought out aims, learning outcomes, anticipated problems and minute-by-minute details on procedure. In contrast, many experienced teachers will usually just write a brief running order as a lesson plan for their regular, unobserved classes.